Over a long enough timeline, every quality company faces a reckoning. Quality companies tend to carry premium valuation multiples. The market is right to have lofty expectations for companies with attractive growth prospects and high returns on invested capital. The moment those expectations are challenged, however, investors typically sell first and ask questions later. This action is not always irrational.

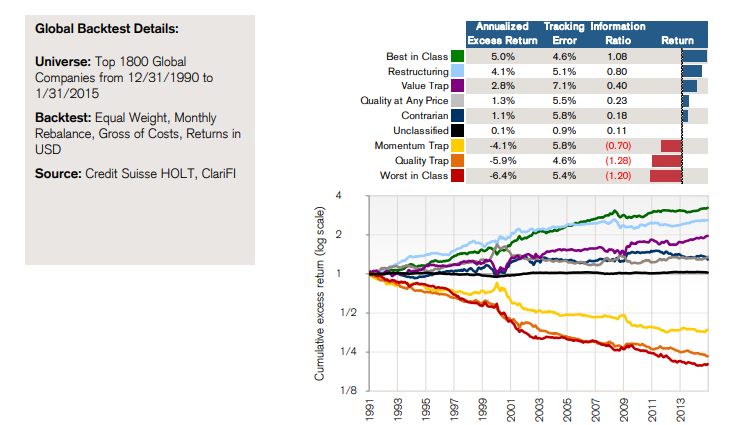

Research done by Credit Suisse HOLT (picture 1) looked at the performance of different investment styles across the largest 1,800 global companies between 1990 and 2014. The “best in class” group – those companies scoring in the top 40% of the sample in HOLT’s quality, momentum, and valuation metrics – was the best performing cohort.

Sounds good for quality, right? However, the second-worst performing group of the nine studied were “quality traps” – companies scoring in the top 40% in quality, but in the bottom 40% in the momentum and valuation metrics. Quality traps stay expensive as their fundamentals deteriorate. This cohort’s performance only just eclipsed the “worst in class” group, which ranked in the bottom 40% in all categories.

Put another way, the quality factor has a wide dispersions of outcomes. If you pay for a ruby but get a rhinestone, you’re not going to have a good outcome. And in the market, you don’t know for years if the ruby you paid for is actually a ruby or a rhinestone. Therefore, at the faintest hint of rhinestone, the market reacts sharply against ruby-priced businesses.

No one wants to own a quality trap, but these drawdowns in quality companies also present opportunities for investors who have conviction in the strength of the underlying business.

How might we do that? Let’s start with what the market is telling us when a company’s stock has a big drawdown. It’s saying the company’s future cash flows will be lower than what the market price suggests or the risks associated with those cash flows are underappreciated.

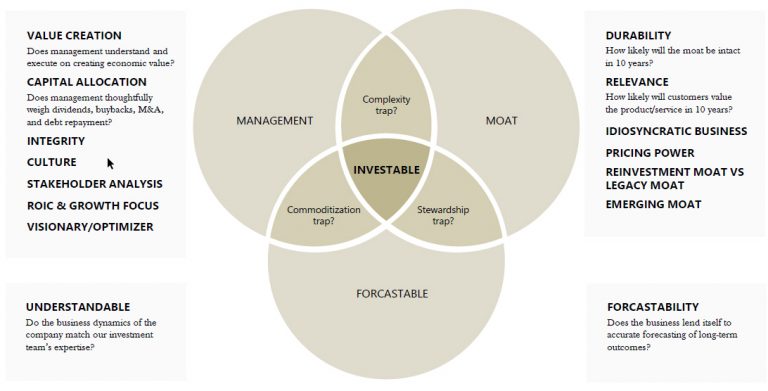

Picture 2 is one of investment philosophy proposition – anchored in moat, management, and forecastability – is designed to respond to such challenges.

First, a moat allows a company to sustainably generate ROIC above its cost of capital and produce more distributable cash flow for a given level of growth. Having a deep understanding of the company’s moat sources helps us evaluate the impact of the event on the underlying business. If we conclude the moat is intact despite new information dragging the stock lower, we’ll be more likely to hold – or even buy more.

Moats also give management teams time to respond to new challenges. But what management does with that time is critical, and especially so in a pinch. If they are poor capital allocators, have too much debt, or oversee a bland or even destructive corporate culture, a crisis will only exacerbate those issues and the moat will erode. As such, we aim to avoid low-caliber management teams.

Finally, the better we understand the company’s unit economics – how the company turns revenue to profit for each unit sold – and its key metrics for success, the more likely we are to recognize material versus transitory impacts.

Once we lose conviction in a company’s moat, management, or forecastability, it's the time to exit our position. Others might successfully invest in “turnaround” businesses, but it’s not the game we play.

All quality companies have large drawdowns at some point, so we as long-term investors should be ready for such occurrences. The less we allow price swings to determine the narrative and instead focus on core business performance, the better our long-term investment performance should be.

Random tag

$TOTL $IPCC $CASS

1/2