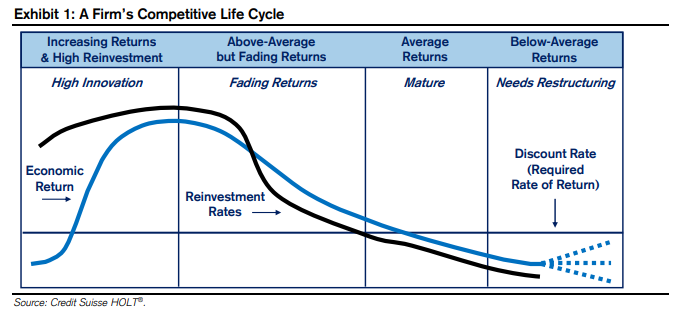

Investors correctly assume that every company has a lifecycle, as illustrated in the chart below. Business 101 teaches that after a phase of high growth and returns, the company eventually faces declining prospects due to increasing size or competition.

But there is no time limit on the x-axis. The cycle could take over a century – well beyond any reasonable investment time frame – or it could play out over a year. If you think a company’s above-average returns could last for a century and they end up lasting a year – or vice versa – you will not be happy with the outcome.

This is where moat analysis comes into play. A company without a moat will not be able to keep competition at bay for long, and the game will end up being a brief affair.

You want to look for ROIC machines that continue to generate returns on invested capital above their cost of capital for long periods. For this type of performance to be possible in the first place, the company has to have some structural advantages that peers fail to replicate.

Just as important is analyzing the company’s relevance. How likely is it that the company’s products and services will be at least as relevant to its customers a decade from now? It is not an easy question to answer, but it can make all the difference.

Relevance should be thought of in terms of depth and breadth. Depth is making each unit more valuable to existing customers, and breadth is acquiring new customers who will find the product relevant in their own lives.

Consider the following comment from legendary investor Peter Lynch in a 2019 Barron’s interview:

“You want to be in [the stock] in the second inning of the ballgame, and out in the seventh. That could be 30 years. Like the people who were really wrong on McDonald’s. They thought they were near the end, and they forgot about the other seven billion people in the world.”

Put differently, McDonald’s increased the breadth of its relevance to billions of customers outside of the United States and lengthened the innings of its game.

Companies can also lengthen innings by delivering innovations that delight customers in ways that would have been unpredictable for any reasonable forecaster at time zero. If you researched Google at its IPO in 2004, for example, Google Cloud had yet to be created. YouTube wouldn’t be launched for another year and Google wouldn’t acquire it until 2006.

When Procter & Gamble went public in 1890, it was already a 52-year-old company. The stock offering, as described in a July 16, 1890 New York Times article, noted that:

“The company has been formed for the purpose of acquiring and carrying on the well-known soap, candle, oils, and glycerine manufacturing business.”

130 plus years later, P&G is still selling soap, candles, and glycerin, but if it were still just selling those items, it would have likely faded into obscurity by now. Major internally generated product launches like Pampers diapers, Swiffer mops, Tide detergent, and Crest toothpaste provided bursts of propulsion that extended P&G’s overall growth.

Conversely, just as companies can extend their innings by widening their economic moats and increasing the depth and breadth of their products’ relevance, innings can be shortened by eroding moats and fading product relevance.

As Lynch advised in the above quote, you don’t want to own companies in the late innings as it can spawn low-growth risks. Companies growing at stall speed – which we define as sub-GDP growth – may become desperate in their capital allocation decisions to regain growth status and are generally not exciting places where talented people want to work. Finance textbooks advise companies in this stage to throw off cash and accept that the business is shrinking, but in practice, few management teams or boards are comfortable admitting defeat.

A large bulk of a company’s intrinsic value depends on its terminal value, or its theoretical steady state. Consequently, the more confidence the market has in a company’s ability to deliver a certain level of growth and ROIC in its terminal phase, the higher the multiple the market should be willing to pay for that company, all else equal.

As investors, we love to follow these types of companies. And, beyond exceptional cases, these sorts of companies are regularly undervalued in the market because investors are worried that the innings are moving faster than they are.

When many risks became manifest, investors need to remember to consider what could go right with a company as much as what could go wrong. Focus on companies set up to play games that could last for decades.

Random tag

$TSPC $KIJA $NAIK